Election Problems in Northampton County, PA in November 2023

Northampton County, Pennsylvania had a technical issue which negatively impacted the election on November 7, 2023. I will explain what happened, the technical details, and the implications from the point of view of an election technology expert. Thank you to the poll workers, witnesses, voters, and journalists who shared their stories about election day.

Background

Northampton County is on the eastern edge of Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia. It has a total population of around 312,000 and around 219,000 registered voters.

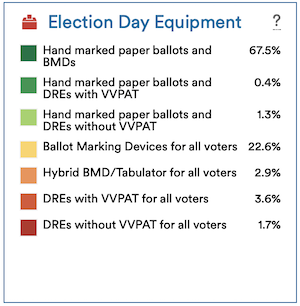

Northampton uses the ES&S ExpressVote XL for all voters in the county. The EVXL is a voting machine with a large touchscreen and a device on the side that prints ballot information onto a narrow card, displays the card for the voter to review, and scans the card to count the votes. It is an "all-in-one hybrid voting machine" because it has a ballot marking device (BMD) and a tabulator inside the same device.

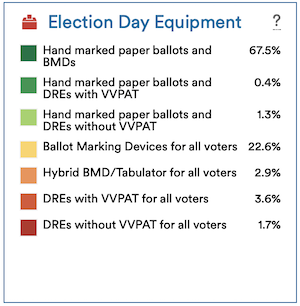

This type of voting machine is relatively uncommon. It is far more common for BMDs and tabulators to be separate devices. However, there are many EVXLs in use, most notably in Philadelphia and Delaware. Verified Voting reports that hybrid BMD/tabulators are used by 2.9% of registered U.S. voters, most of which are using the EVXL.

The ballot card printed by the EVXL has barcodes at the top and human-readable text below. (Example) When a ballot is cast, the EVXL only reads data from the barcodes. It does not read data from the human-readable text. The ES&S barcodes contain numbers that are references to vote selections in different contests. 1 barcode = 1 vote.

Northampton purchased the EVXL in 2019 and currently owns around 300 of them. There were major technical problems when Northampton first used the EVXL. One problem was screen calibration issues that prevented voters from voting how they wanted. A second problem was that the ballot definition file, which configures each device for an election, was incompatible with the EVXL, causing it to incorrectly assign votes during scanning and tabulation. At the close of the polls, the EVXL reported 0 votes for some candidates who definitely had votes. Many of these candidates eventually won their contest when the ballot cards were counted using different scanners.

All Pennsylvania counties routinely perform pre-election Logic & Accuracy (L&A) Testing. L&A testing should have detected an error in the ballot definition file. But the testing in this case was so poorly done that no one noticed that some candidates had 0 votes at the end—and with around 300 opportunities to notice it.

Five years later, for the November 2023 election, Northampton outsourced the creation of the ballot definition files for this election to ES&S, the manufacturer of the EVXL. Northampton also performed pre-election L&A testing with assistance from ES&S and used a "test deck" provided by ES&S.

A test deck is a collection of predetermined ballots to be cast on each device during L&A testing. A test deck should be thoughtfully designed to test for errors in the ballot definition file and to ensure that votes are being correctly assigned to the correct candidates. For example, if a test deck of 30 ballots was designed to have a total of 20 votes for Candidate A and 10 votes for Candidate B, then the L&A testing will cast those ballots and expect the results to show exactly 20 and 10 votes for those candidates.

Northampton sent a certification to the PA Department of State that they completed L&A testing and all 300 EVXLs passed the tests. Everything seemed to be in order and ready for election day.

Summary of Election Day Events

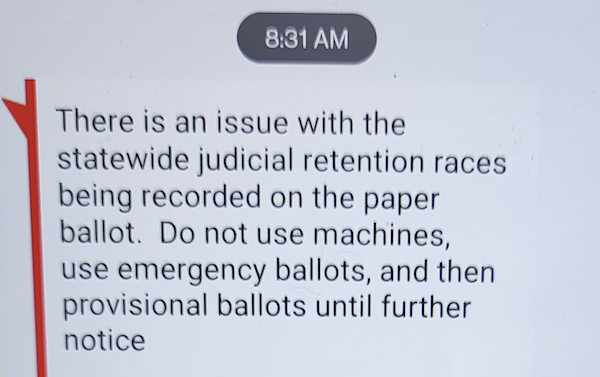

Polls opened at 7:00 AM. According to the County, at 7:15 AM two precincts (out of 156) reported that their EVXLs were printing ballots that sometimes did not match the selections the voters had made on the touchscreens. Over time, voters and poll workers circulated reports of this issue and their attempts to work through it. Some voters were asked to come back later, some were given emergency paper ballots to vote on instead, and some were advised to select the opposite of their vote choices on the EVXL's touchscreen so that the printed paper ballot would be correct. Many voters expressed concern about the integrity of their ballot and of elections generally.

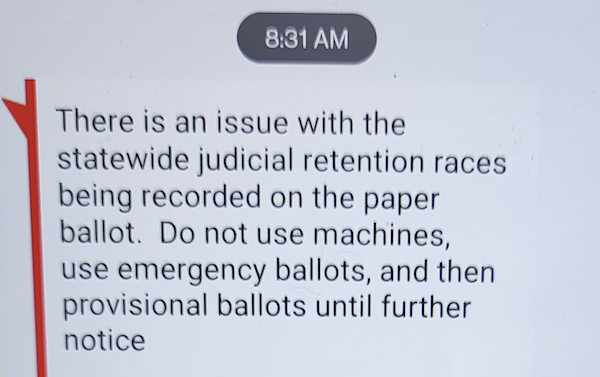

At 8:31 AM, the County sent a text message to all precincts:

Precincts switched to issuing emergency paper ballots, but they had little supply and quickly ran out.

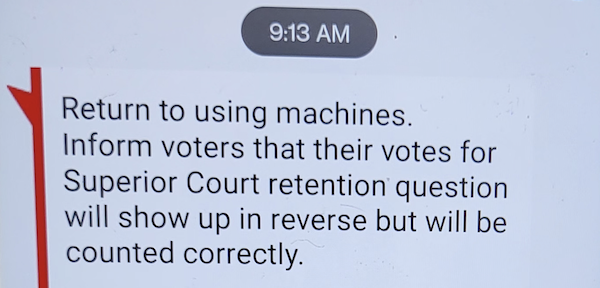

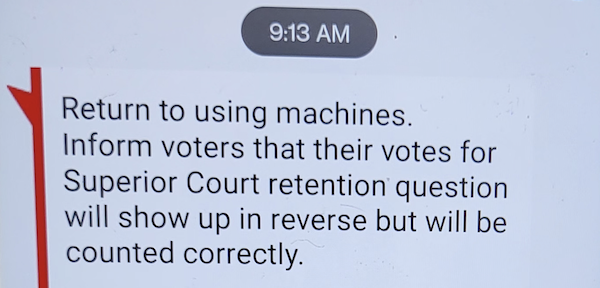

At 9:13 AM, the County sent a text message to all precincts:

Between 10:00-11:00 AM, the County asked the Court of Common Pleas to order poll workers to warn voters about the issue, which it did. The County also stated their intention was to swap the vote totals at the end, but the Court was not asked to authorize that plan.

In the afternoon, the Northampton County Republican Party also went to Court over the issue. At 4:09 PM, the Court ordered modified intructions for poll workers: voters should use the EVXL and check their ballot cards; if a ballot is wrong and the polling place has another EVXL, the voter should try using it; otherwise the ballot gets spoiled and the voter gets an emergency paper ballot. A third Court order followed at 6:29 PM, threatening poll workers with "penalty of contempt" if they did not tell voters to check their paper ballots to be sure it matches the vote on the machine.

After the election, the County announced that approximately 2,160 emergency paper ballots were cast and 234 provisional ballots. The unofficial election results show 47,015 ballots were cast on election day.

This summary is a condensed version of the longer timeline of events that has additional details, photos, and links to the court orders, press conference video, and press releases.

The Error: Reversed Text Labels

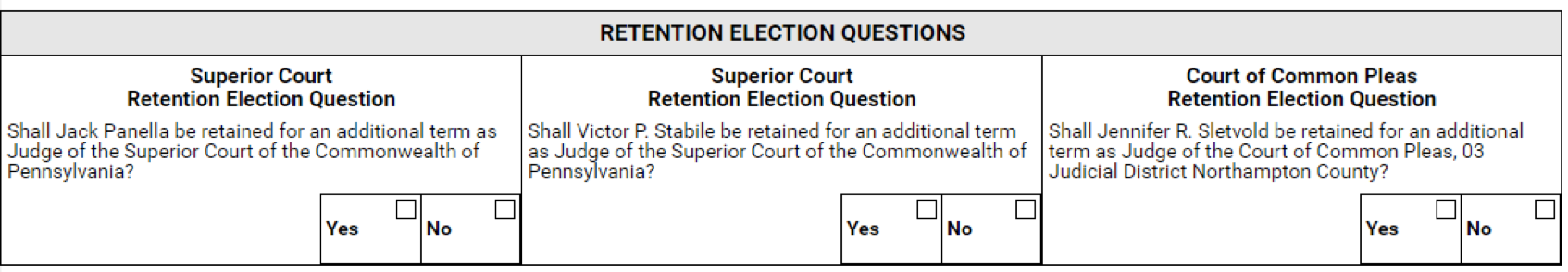

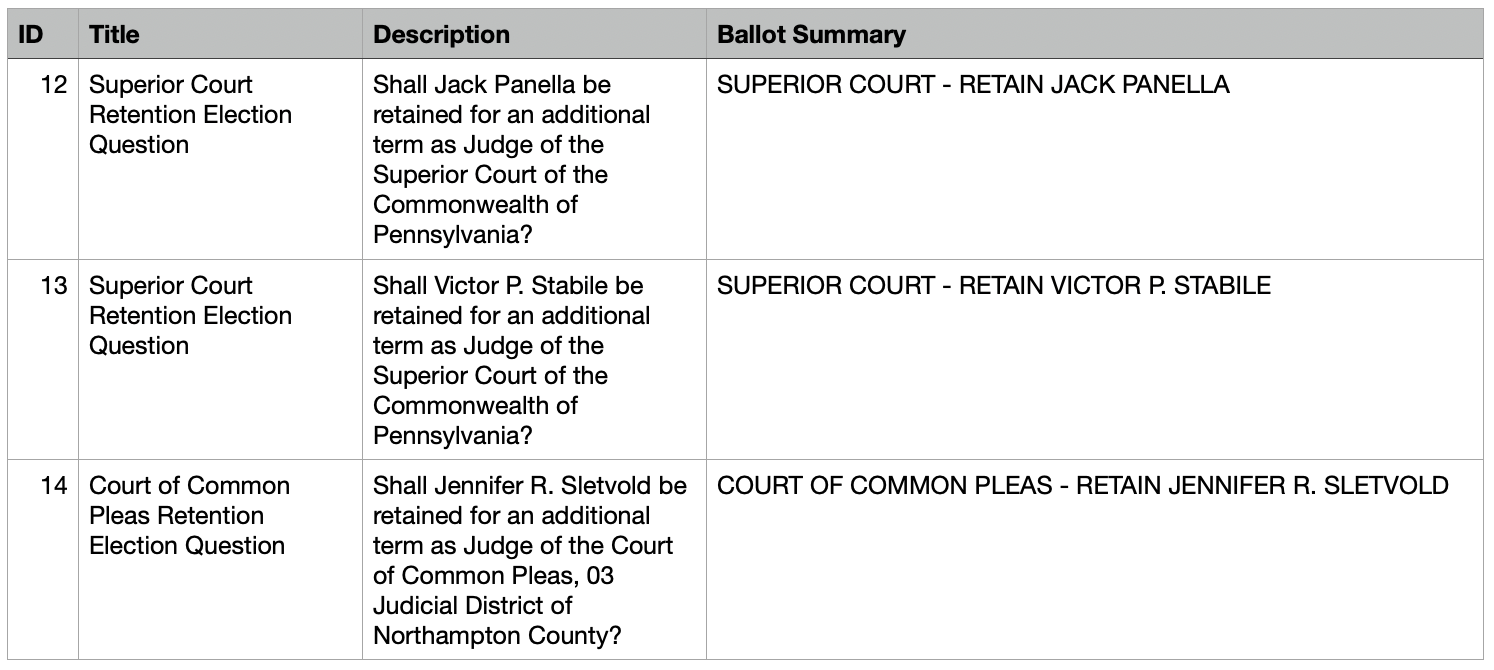

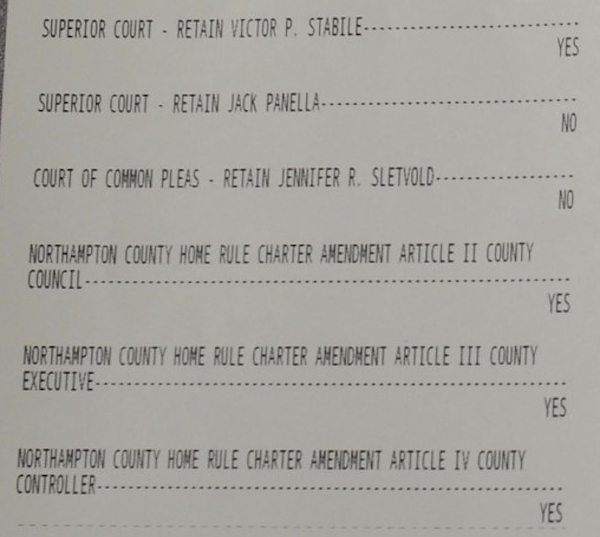

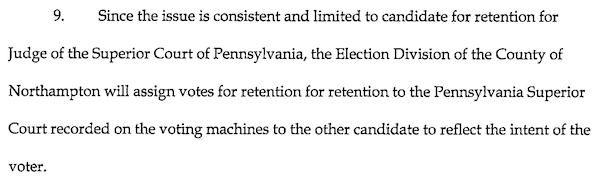

Pennsylvania votes on judicial retention—should a judge be given another term in office. In this election, Northampton had three judicial retention contests on the ballot. This is how they appeared on the EVXL touchscreens, in this order: Panella, Stabile, Sletvold.

Voters would touch the EVXL touchscreen to make vote selections. The screen would indicate each choice as expected. After making all selections, voters would press a button on the EVXL touchscreen to print their ballot.

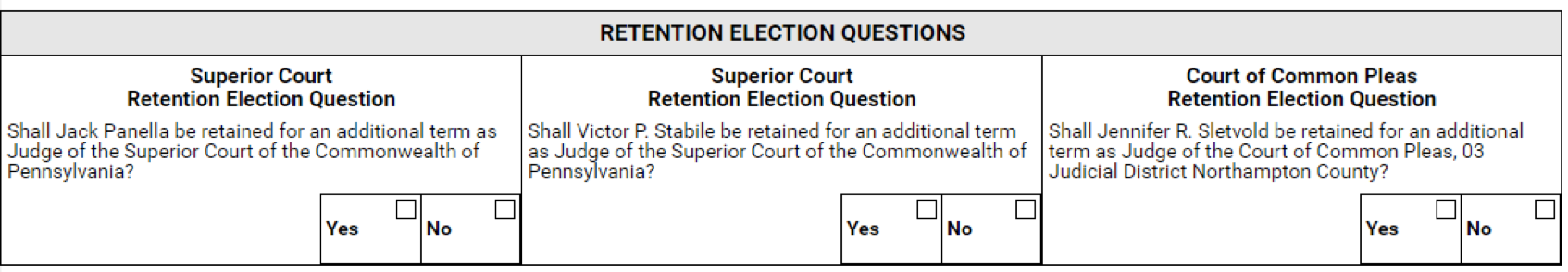

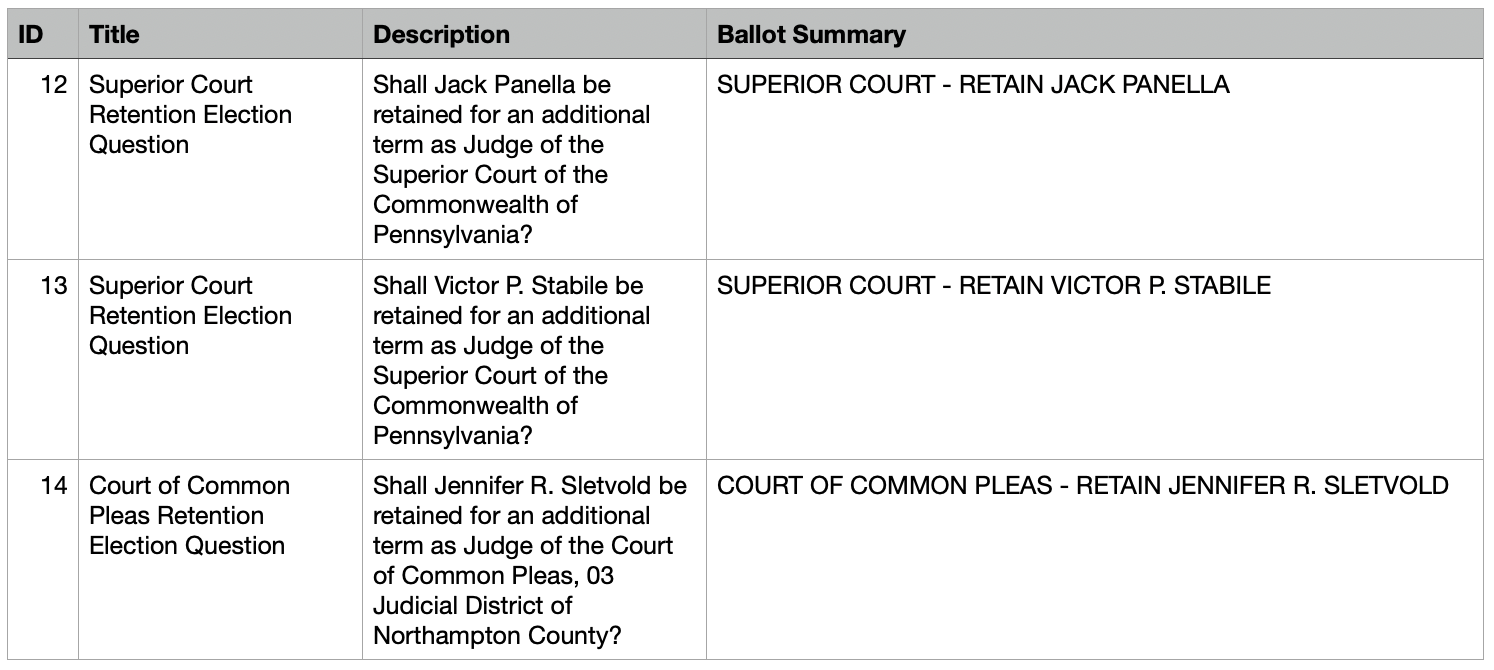

The EVXL prints a summary of a voter's screen selections on the ballot card. The text of the judicial retention contests is too long to print on the card, so each contest is assigned summary text to use for printing. Both the long and short text is stored in the ballot definition file. It may be helpful to think of it like a spreadsheet table.

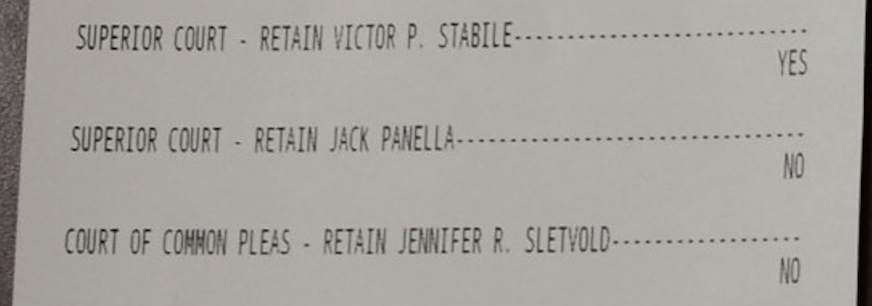

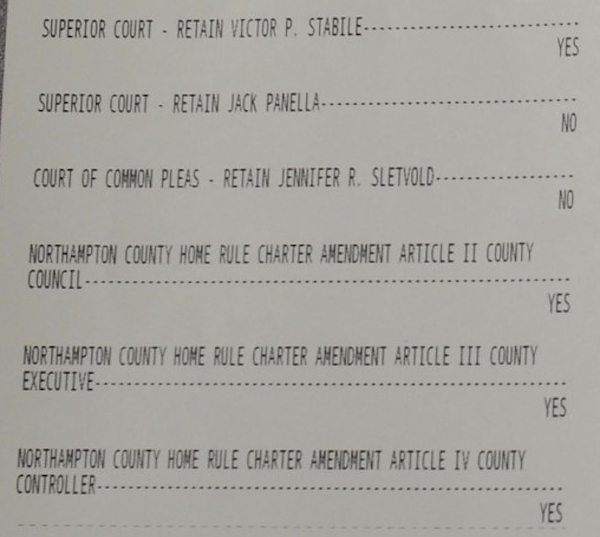

The cause of the error was a mistake during the creation of the ballot definition file that configures each device for this specific election. ES&S reversed the ballot summary text used for Judge Panella and Judge Stabile. It was likely a simple data-entry error. As a result of the mistake, for all ballots printed by the EVXL, the contest names appeared in the wrong order: Stabile, Panella, Sletvold.

If a voter voted YES for all judges or NO for all judges, then the voter would not notice the change. But if a voter voted YES for Panella and NO for Stabile, or vice versa, then the ballot summary would show the reverse of their screen choices. This explains why some voters reported their ballots were wrong while others did not.

The YES/NO in each position was correct, but the summary text labeling the YES/NO was swapped. The YES and NO votes in any single contest were not swapped; it swapped the contest labels.

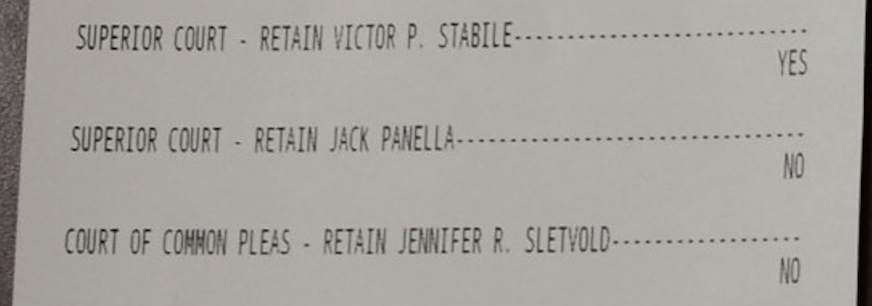

The results tapes that show the vote totals for each polling place also show a correct tally for each contest based on its position on the ballot, but also use the wrong labels on each contest.

Results with the error might look like:

SUPERIOR COURT - RETAIN VICTOR P. STABILE

YES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

NO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

|

SUPERIOR COURT - RETAIN JACK PANELLA

YES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

NO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

|

When those results without the error would look like:

SUPERIOR COURT - RETAIN JACK PANELLA

YES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

NO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

|

SUPERIOR COURT - RETAIN VICTOR P. STABILE

YES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47

NO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

|

The L&A Testing performed before the election did not detect this error. The tests did not examine any of the printed ballot cards where it may have been directly visible. The tests only examined the totals at the end of the test (like in the above examples). If the test deck cast an equal number of YES and NO votes for each candidate then the totals would seem correct, just listed in the wrong order. That's a subtle change that is easy to overlook. If the test deck cast unequal votes for each candidate, then it means the testers didn't notice that the results were obviously wrong during the tests of 300 EVXLs.

The technical details of the 2019 and 2023 errors are different. The first was a problem with the EVXL's ability to tabulate. The second was a problem with the EVXL's ability to print a correct ballot. However, they have similarities. Both errors were caused by faulty device configuration and insufficient L&A testing.

Are the Barcodes Wrong Too?

The human-readable text was wrong, but the EVXL never considers that text when counting the votes on a ballot. It counts exclusively from the barcodes. If the error diagnosis is correct, then the barcodes should still hold correct values for the intended candidates.

I wrote a long explanation of how to decode the ES&S barcodes several years ago.

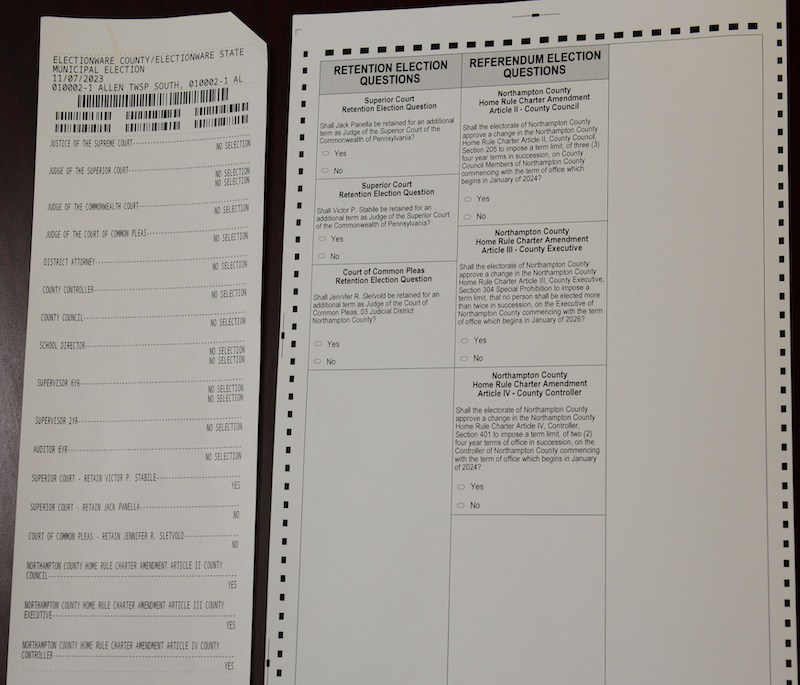

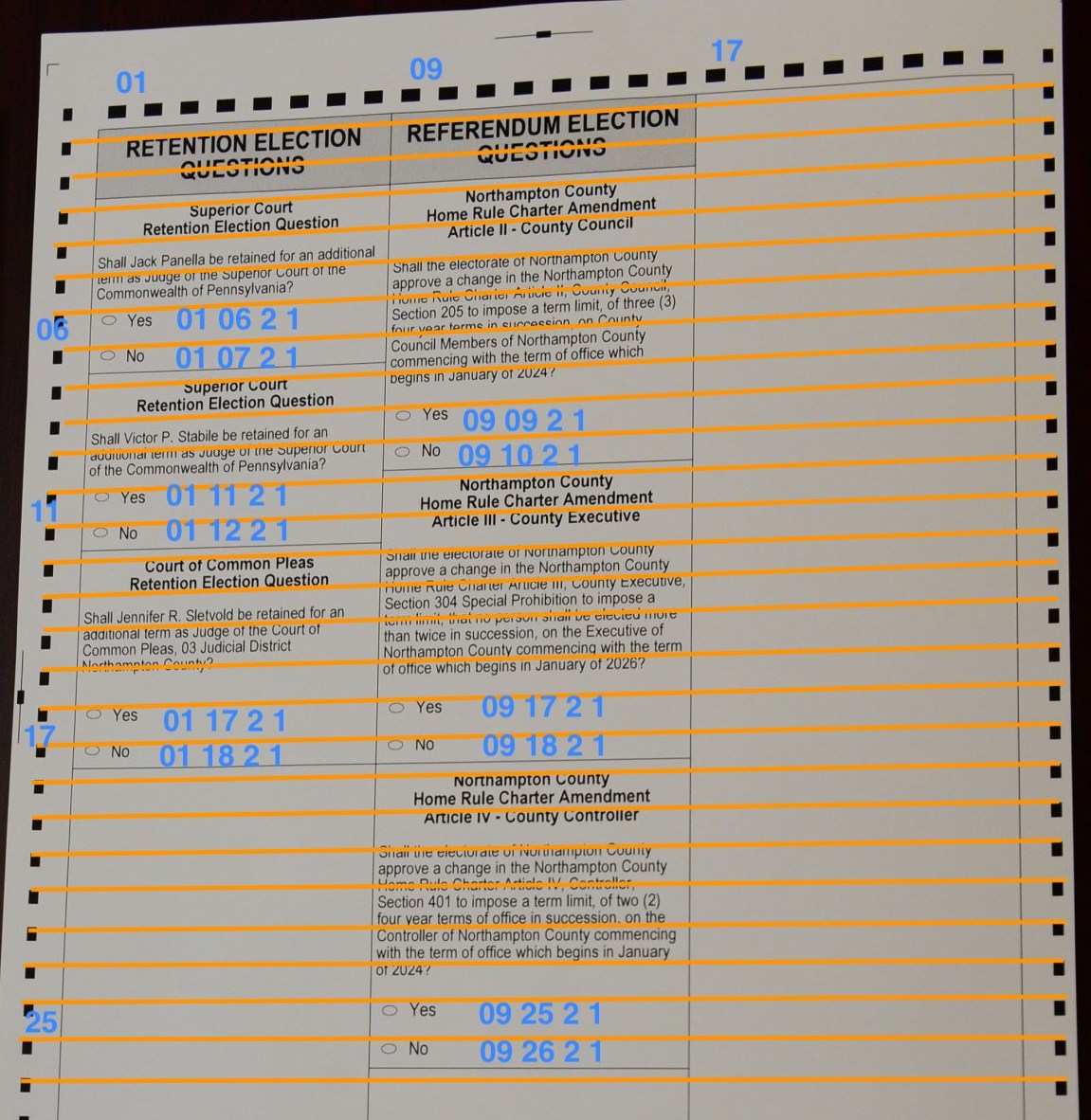

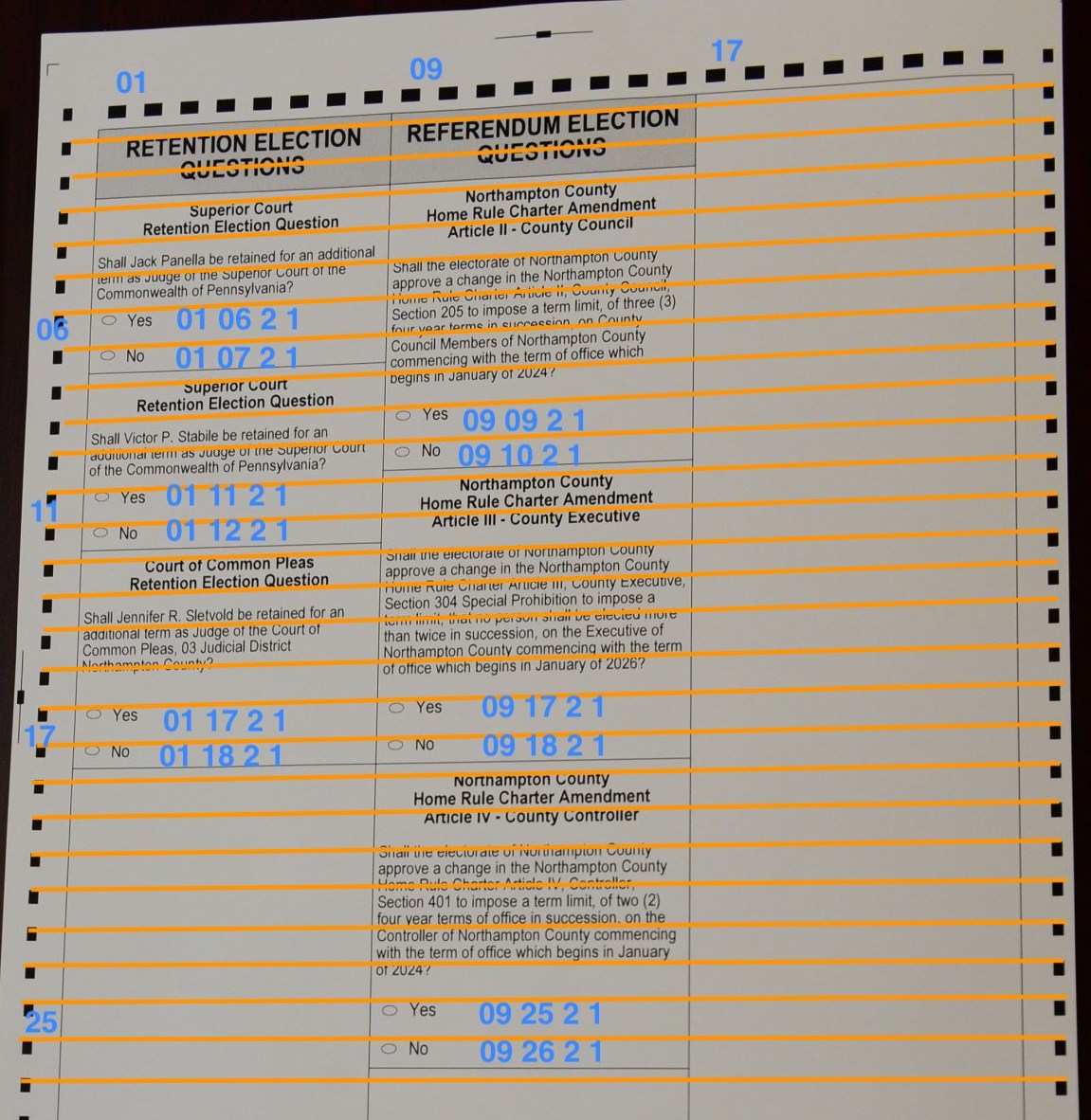

You need a barcode scanner and an example of a full-face paper ballot (with ovals to mark by hand) from the same precinct for reference. The County provided the news media with an example of a ballot card that has the issue and the matching full-face paper ballot. Those can be used to confirm that the barcodes are correct.

The barcodes in the photo can be scanned with a barcode scanner. Here are the decoded values for the six smaller barcodes, which represent votes in the six contests where selections were made.

010621 011221 011821

092521 090921 091721

These six numbers are coordinates on the full-face paper ballot. The first two digits are the column number, the second two digits are the row number, and the last two digits are the ballot side and page number. At that location, we can expect to find an oval for a contest selection. So "010621" means the same thing to the ballot scanner as a filled oval positioned in column 1, row 6, on side 2 of a one-page ballot.

It is helpful to draw lines on the photo of the full-face paper ballot to reveal the grid for the coordinates. I drew horizontal lines (in orange) between the square timing marks in the left and right margins to show the rows. I could have drawn vertical lines to show the columns, but it wasn't necessary. The ovals are either in columns 1 or 9. Finally, I added the coordinates for each oval (in blue) to make them easy to find.

The barcode values can now be used to locate the corresponding ovals. The barcodes are not printed in order on the ballot card so I sorted the values from lowest to highest, which is the same order they appear on the full-face ballot.

010621 = Retain Panella ..... YES

011221 = Retain Stabile ..... NO

011821 = Retain Sletvold ..... NO

090921 = Amend Article 2 ..... YES

091721 = Amend Article 3 ..... YES

092521 = Amend Article 4 ..... YES

These are the votes that the scanner should interpret from those six barcodes. These results match the pattern of YES/NO votes in the human-readable ballot summary printed below the barcodes in the photo.

The barcode values support the explanation of the error. The barcodes are correct. The text is wrong. The contest labels have been switched.

Implications

The events in Northampton County raise several important points that are worth examination and discussion.

Did the problem ultimately have a material effect on the election outcomes?

This is the most important question to ask after any election problem. Did the problem change the winners? Every election has small problems that do not change the election outcomes. There are two complications to consider when sorting out this mess.

First, some voters may not have cast votes according to their intent. Some voters may have been turned away and not returned. Some voters may have stayed home after hearing about the issues. Some voters may have skipped voting in those contests. Some may have voted the opposite of what they wanted on the touchscreen in order to get a printed paper ballot that matches their intent, as one report said. If they did, those barcodes will contain votes that are the opposite of their intent and will be counted that way. We can hope that these are small numbers of voters that would not have a material effect, but we cannot know. Missing or wrong votes are not correctable after the fact.

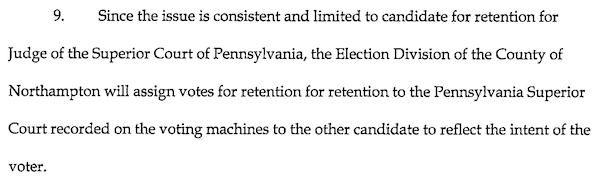

Second, the totals listed in the printed records (poll tapes, reports) and digital records (USB drives) will be wrong. I am not an attorney, but I see some thorny legal issues about simply swapping the reported results around to address this issue. The PA election code is old, infrequently updated, and full of ambiguities. It does not have easy remedies for problems like this. Certainly, the idea of a anyone independently deciding to "adjust the results" makes everyone uneasy. Any resolution needs to be legally well grounded.

Northampton County told the Court of Common Pleas they will "assign votes...to the other candidate", but did not cite any law that allows it. I am not aware of any such law and, to my knowledge, no court has endorsed this course of action. Witnesses say that the precinct results report had the correct contest labels and canvassers were swapping what is on the paper results tapes that were printed at the close of the polls as they reconcile them. The unofficial election results do not indicate if the results have been swapped or not, but I presume they have. Soon, election officials will be asked to certify that the results presented to them are correct. Are they correct if the letter of the law is followed? I don't know, but it seems worth finding out before signing anything.

The paper ballots are meant to be the reliable record of each vote, but here they are as legally complicated as the vote totals. They contain two separate representations of a vote that disagree. Which one should control? One view is that the barcode is the controlling vote because the certified results always come from the tabulation of barcodes. It is basic logic: if the official vote is anything besides the barcode, then every election would pick winners without counting the votes. Another view is that the text is the controlling vote because it is the only thing each voter could verify was correct before it was cast. (This is the view that post-election audits take.) The PA election code is not helpful in resolving it. Act 12 of 2020 made barcode/summary ballots legal and redefined a valid vote selection as a mark next to a candidate name or "BY OTHERWISE INDICATING A SELECTION ASSOCIATED WITH THE CANDIDATE". This broad definition allows any indication of voter intent, and includes both the barcode and the text.

There's also a pragmatic answer that is not at all satisfying and offers no help if there are similar errors in the future. Swapping the results of these contests probably does not matter for determining the outcomes. Both of these judges are likely to be retained. Historically, only one PA judge has ever not been retained. The issue was not that YES votes became NO votes and NO votes became YES votes. The contest results were swapped entirely. So the totals might be different when swapped, but the winners of both contests will not change. It would be a very different scenario if popular and unpopular ballot measures had been switched. (This type of BMD also requires ballot measures to use shorter summaries.)

Was this issue evidence of election fraud, rigging, or hacking?

No. Not in this election. Not in past elections.

This issue was almost certainly an accident. Northampton contracted ES&S to create the ballot definition files for the EVXLs. That task is mostly data entry, similar to filling out many spreadsheets. The task can be complex though, because some contests will appear on every ballot in the county and other contests only appear on the ballots in a few of the 156 precincts. It requires a lot of careful organization. This was an easy mistake to make.

This issue also didn't benefit anyone. These contests were not highly contested. They weren't even contests between two candidates. Judges are usually retained by a wide margin. I am confident that swapping totals between these two contests will cause two judges who would have won to... still win. That does not look like fraud, rigging, or hacking.

I take fraud, rigging, or hacking seriously and never casually dismiss it. As Carl Sagan cautioned, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." All the evidence in this case points to an accidental mistake.

A Barcode-Text Mismatch

Experts and advocates have been warning for years about ballots that record votes as both barcodes and human-readable text. Barcodes are not verifiable by the voter, even with a barcode scanner in hand, yet barcodes are the only thing being counted on election night. No voter can verify that the vote they are casting is what was intended. There's a paper record but it is still a black box, just like a paperless voting machine. Voters routinely say barcodes make them uneasy and they don't trust them. Plus, there's the possibility of legal ambiguity from dueling votes on the same ballot, which was described previously.

Proponents of these systems have rebuffed these concerns. They say the voter can verify the human-readable text instead. They claim the text is a reliable proxy for the vote stored in the barcode. The possibility that the barcode and the text would ever disagree is dismissed as an unlikely hypothetical.

But here we are! All it took was one small data-entry error to knock down that house of cards. The human-readable text is not a reliable proxy for the votes stored in barcodes. A BMD-printed ballot may not mean what the text says it does.

Many ballots were cast in a real election in Northampton County where the barcodes contain one vote and the human-readable text contains a different vote.

It would be a mistake to write this off as a minor "clerical error". This fiasco reveals that barcodes infringe on every voter's right to cast the vote they intend. Voter verifiability and ensuring ballots are cast as intended are bedrock principles of modern elections for exactly this reason. We need confidence that the paper ballots are trustworthy evidence of voter intent if we are to ensure election outcomes reflect the will of the voters. These voting machines produced untrustworthy evidence of voter intent instead. It is an unfortunate fact that no Northampton voter knows what vote they cast in any election contest, not just the judicial retention contest. Voters can only hope that their votes match what they can read.

A barcode-text mismatch due to a data-entry mistake is an accident that may be repeated in future elections, and in other jurisdictions. And if a mistake in the configuration files can create a barcode-text mismatch, then a malicious attacker can too. An attacker could strategically plan changes to create far bigger problems.

BMDs for All Voters

Source: Verified Voting

In Northampton, the EVXL is a hybrid BMD/tabulator used by all voters. The November 2023 problems are unique to BMDs and are magnified by using them for all voters.

According to Verified Voting, 25.5% of U.S. voters vote by using a BMD or Hybrid BMD/tabulator for all voters. Maps at that link show that only a few states and counties have chosen BMDs-for-all, but some of them have many registered voters.

Most voters in the U.S. vote a different way, by using hand-marked paper ballots fed into a scanner/tabulator with BMDs available for anyone who wants a machine's help marking a ballot. Nationwide, 69.2% of voters vote primarily using a hand-marked paper ballot. In Pennsylvania, where each county chooses their own voting system, 69.6% of voters vote this way.

This error and all of the problems that resulted from it are unique to BMDs. Voting systems where most voters use hand-marked paper ballots do not have such problems. First, full-face paper ballots (ones with ovals to fill) only have one representation of each vote on the ballot. No possibility of a barcode-text mismatch, no legal ambiguity. Second, full-face ballots show the full text for all contests and candidates. There's no need to use shorter alternative text that might be different. Third, the voter does not need to take a second action to verify that the ballot printed by a machine is correct. Fourth, there is no barcode to frustrate voters' ability to verify that each vote being cast is correct. Fifth, if voting machines malfunction, voters can continue to vote using a sufficient supply of pre-printed ballots and the ballots will just be scanned later.

Professors Appel, DeMillo, and Stark make a compelling argument that BMD-printed ballots are always unreliable evidence of voter intent in their paper, "Ballot-Marking Devices Cannot Assure the Will of the Voters". Their conclusions are supported by studies that show that voters do not reliably check the printed ballot or detect errors. A good example is "Can Voters Detect Malicious Manipulation of Ballot Marking Devices?" by Dr. Bernhard and others.

The events in Northampton reinforce the observations in these papers. Some precincts voted for 1.5 hours without any voter noticing the error on the printed ballot. If these voters did not check their ballots, it is impossible to know if any of the votes on those ballots were as they intended. The voter or the EVXL may have made a mistake in other contests that wasn't noticed.

Once the judicial retention error was noticed and reported by a few voters, it was difficult to address. It was only possible to take all 300 EVXLs out of service for a short time. The County ultimately returned to using voting machines they knew were malfunctioning and voters cast ballots with known errors. There were no other good options.

The barcode-text mismatch is a more obvious issue, but we should not overlook how the decision to use BMDs for all voters opened the door to these problems. Requiring voters to take an extra step to check their ballot carefully—which they don't do reliably and can't do effectively—reduces the trustworthiness of the paper ballots and harms the ability to use them as reliable evidence for recounts and audits. (Which was the whole reason for replacing paperless voting machines with new ones that use paper ballots in the first place.)

Resilience

The events in Northampton contain lessons about managing the risks of technical failures during elections.

Resilience is the ability of a system to recover from adverse events. A good example of resilience is a skydiver's backup parachute. If the primary parachute fails, the backup parachute allows the skydiver to recover from the adverse event and land safely.

Elections have unique challenges that make resilience a primary election security concern. Every election day has a limited number of hours. Each precinct has an allocation of voters to serve during those hours. Some voters can only vote at certain times and may not be able to wait or to come back later. Long lines frustrate voters and can depress voter turnout. Technical failures can have significant impacts on elections—on the process, the outcomes, and voter confidence. If something goes wrong, it is critical to have a solid backup plan in place.

Voting systems in which all voters use a BMD increase the risks of a technology failure. A BMD is an expensive pen that may not always work or may not work as expected, yet voters rely on it to cast a ballot. Voting can be seen as two actions: marking the votes and counting the votes. If counting technology fails, counting can be delayed or performed manually. But if the marking technology fails, emergency paper ballots are the only option; voters can't write barcodes.

These events show that Northampton County did not adequately plan for a county-wide system failure. Sluggish responses and unclear instructions made a bad situation worse. Poll workers do not appear to have been well prepared for it. There were insufficient numbers of emergency paper ballots and no plan to get more quickly when needed. There was no plan to keep emergency paper ballots secure throughout the election day. If it had not been possible to return to using the EVXL at 9:13 AM, I don't know what the County would have done, and I doubt they do either.

Jurisdictions relying on BMDs to function need robust resilience plans in place. Extra resilience planning, as well as more burdensome L&A testing, is a hidden cost of ownership for BMDs. It can be tempting to believe the extra work is not worth the effort and expense, but you don't need a disaster plan until you suddenly do.

Voter Confidence

This incident has shaken voter confidence that elections are fair and the outcomes are correct. Poll workers say that voters told them so clearly on election day: "It perpetuates the notion that elections are rigged." It is already being circulated online as "proof" of wide-spread rigged elections. (It is not.)

Voter confidence was also harmed when poll workers were ordered to tell voters to check that their ballot is correct but also to imagine that some parts will be switched around later. The voting system seems arbitrary and opaque, not trustworthy.

Northampton residents view this incident with the failures in 2019 still fresh in their memories. Some say they feel burned twice and worry it will happen again.

These events cannot be undone, but we can recognize that voter confidence has been impacted both by actual events like this and by disinformation and then take steps to restore the public's trust.

Recommendations

These are my top recommendations on how to productively move forward after this incident.

-

Northampton County should ask the Pennsylvania Secretary of State for guidance about the legality of swapping the vote totals. They should get a judge to provide a court order if necessary. Finding a resolution while carefully following the law is important for rebuilding voter confidence. The public should not feel the resolution was arbitrary. A bad precedent should not be set.

-

Northampton County should begin a full and transparent investigation. The purpose is not only to discover what happened generally but to learn from the many details of this experience to improve processes and prevent future problems.

After the problems in 2019, the Northampton County Council asked ES&S to do an investigation and give them a written report. ES&S gave an oral overview, with few technical details, that mostly absolved their hardware and software from blame. It had little value for Northampton.

ES&S should assist with an investigation but Northampton will be better served by having someone else lead it. The Northampton County Election Board, the PA Department of State, the U.S. Election Assistance Commission's Quality Monitoring Program, or independent election experts are all good choices. A useful investigation is one that results in a written report that describes the root problem in detail and also provides recommendations for concrete, actionable improvements. There is a lot to learn from this incident.

-

I do not think it is productive to consider firing anyone. There is plenty of blame to go around. Experienced election staff are in short supply at the moment. It is more productive to be honest about the series of failures that happened and learn from them. A high-profile election cycle in 2024 is quickly approaching and the County should focus on fixing issues, not pointing fingers.

-

Northampton County should change to a voting system that uses hand-marked paper ballots for most voters and BMDs for voters who want machine assistance. There are many reasons to do it, but taking visible steps to restore the trust of Northampton's voters is at the top of the list.

There are two ways the County could accomplish it. There are advantages to each.

- Starting in the 2024 primary, the County could offer all voters the choice between voting on the EVXL or on a hand-marked paper ballot. Because the EVXL cannot scan hand-marked paper ballots as other tabulators can, the County would need to purchase one ES&S DS200 tabulator for each precinct. The new voting option would also allow the EVXLs to operate in ballot-marker-only mode and should allow the County to leave some of the 300 EVXLs in storage.

- The County could begin the procurement process for a new voting system in 2024. They could consider other vendors, but staying with ES&S would allow them to continue using the election management computers and the central-count scanners they already use. The target date for its first use would be the 2025 Primary Election.

(This is a different recommendation than I would make to jurisdictions who are not using hybrid BMD/tabulators. For most jurisdictions transitioning from BMDs for all voters to hand-marked paper ballots for most voters, they already own all the precinct equipment they need. They just need to leave some of the BMDs in storage.)

-

Northampton County should pressure ES&S to demonstrably improve its quality control measures to prevent mistakes in the ballot definition files that configure each device for the election. This was the second time that a configuration error caused a catastrophic failure. Ballot definition files should be tested by ES&S as part of their contract and then separately by the County's L&A testing. (This was not the only mistake ES&S made: touchscreens were displaying cross-filed candidates in a separate column, but it was fixed before election day.)

-

Northampton County should review and improve their L&A testing. In September 2023, the PA Secretary of State put out a 25-page directive on L&A Testing. The County should review it and compare their testing with it. (The Secretary of State should consider whether the directive needs any updates in light of this failure.)

A hybrid BMD/tabulator voting machine requires testing both the BMD and the tabulator functions. It is important to review ballot cards and not just the result tapes.

Northampton should either work with ES&S to improve the test deck used during L&A testing, so that it is able to detect this type of issue, or learn how to make their own test deck, as some other Pennsylvania counties currently do.

-

Northampton County should improve their resilience plans and poll worker training. They should develop written action plans. Tabletop exercises to walk through various scenarios may be helpful. The plan should provide precincts with more emergency paper ballots and be able to print or distribute more if needed. Switching to mostly hand-marked paper ballots would greatly increase the resilience of the voting system.